In 1825, Thomas Jefferson was asked to write some words of advice for the newly born grandson of a close friend of his; the child was named Thomas Jefferson Smith after the President, as a token of affection.

In his response Jefferson gave some of his dearly-held principles on how to live life to the full, all of which still hold true today. In his letter he responded as follows:

Your affectionate and excellent father has requested that I should address to you something which might possibly have a favourable influence on the course of life you have to run, and I too, as a namesake, feel an interest in that course.

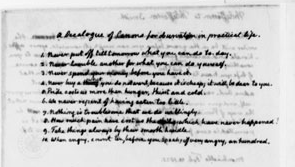

Jefferson ended the letter by writing what he called “A Decalogue of Canons for Observation in Practical Life.” on the other side of the page:

Jefferson ended the letter by writing what he called “A Decalogue of Canons for Observation in Practical Life.” on the other side of the page:

- Never put off till tomorrow what you can do to-day.

- Never trouble another for what you can do yourself.

- Never spend your money before you have it.

- Never buy what you do not want, because it is cheap; it will be dear to you.

- Pride costs us more than hunger, thirst and cold.

- We never repent of having eaten too little.

- Nothing is troublesome that we do willingly.

- How much pain have cost us the evils which have never happened.

- Take things always by their smooth handle.

- When angry, count ten, before you speak; if very angry, an hundred.

It seems that Jefferson put quite a bit of thought into these principles throughout his life; he also gave a very similar list of twelve to his granddaughter. Some of them are his own creation, others he came across from his extensive reading.

The last one in particular, has ended up in many a list of Jefferson quotations. Regarding the eighth one, it is interesting to hear in what he has to say in an 1816 letter to John Adams:

You ask if I would agree to live my 70. or rather 73. years over again? To which I say Yea. I think with you that it is a good world on the whole, that it has been framed on a principle of benevolence, and more pleasure than pain dealt out to us.

There are indeed (who might say Nay) gloomy and hypochondriac minds, inhabitants of diseased bodies, disgusted with the present, and despairing of the future; always counting that the worst will happen, because it may happen. To these I say: How much pain have cost us the evils which have never happened?

Jefferson was 82 years old when he wrote this letter, and must have known his days on earth were numbered – in the letter he writes ‘his letter will, to you, be as one from the dead. The writer will be in the grave before you can weigh its counsels.’ Indeed, Thomas Jefferson passed away the following year on July 4th, the same day as John Adams, and 50 years to the day after the Declaration of Independence was signed. But he includes in the letter this very affectionate remark:

And if to the dead it is permitted to care for the things of this world, every action of your life will be under my regard. Farewell.